A Ritual for Imbolc and a Brigid Miscellany

I’ve been studying St. Brigid and the goddess of the same name for… quite a while now. Years and years. And every time I think I’m ready to say something about the two, I find myself wandering down unexplored paths and never quite getting down to writing. Offering preorders for A Postmodern Witch’s Guide to Imbolc enforced a bit of discipline, and in the wee hours of this morning, I met my self-imposed deadline. If you placed a preorder for the print edition, it’s already on its way to you. I also added the digital edition to the shop today.

Does this mean that I maintained a laser-like focus on the project at hand? Heavens, no. I could spend the rest of my life—I may well spend the rest of my life—trying to understand both goddess and saint. So, without further ado and in no particular order, are some random notes about Brigids. (And, for paid subscribers, a download of a ritual from the zine and the Imbolc Tarot spread in case you missed it.)

1. St. Brigid turned lepers’ bathwater into beer

I swiped this image of St. Brigid with pint, crisps, and foamy mustache from 9 White Deer Brewery in County Cork. This is not an endorsement of their products, as I have never sampled them, and if they want me to stop using this lovely prayer card for boozers, they can let me know.

St. Brigid is a patron of scholarship, poetry, smithcraft, domesticated animals, and dairy products. I get into her association with milk and its many delicious permutations in the zine. What I didn’t mention was how much she loves beer. Maybe it’s worth pointing out here that, for much of human history, beer has been an important—and, significantly, fairly stable—source of calories. To suggest that it was liquid bread is maybe overstating the case, and to be sure the beers of yore had the power to intoxicate, but medieval ales could have an ABV as low as 1% and—like wine—beer was often diluted with water. I mention all this because I don’t want to suggest that the Abbess of Kildare was a party girl, and that running out of beer was a different kind of catastrophe than it may be now. I will say, though, that Brigid as we know her now is associated with many of the human achievements that make life worth living, and I think that this lovely poem 10th-century poem attributed to Brigid expresses this quite nicely. And if you know another saint who turned lepers’ bathwater into beer, please do let me know.

I’d like to give a lake of beer to God.

I’d love the heavenly

Host to be tippling there

For all eternity.

I’d love the men of Heaven to live with me,

To dance and sing.

If they wanted, I’d put at their disposal

Vats of suffering.

White cups of love I’d give them

With a heart and a half;

Sweet pitchers of mercy I’d offer

To every man.

I’d make Heaven a cheerful spot

Because the happy heart is true.

I’d make the men contented for their own sake.

I’d like Jesus to love me too.

I’d like the people of heaven to gather

From all the parishes around.

I’d give a special welcome to the women,

The three Marys of great renown.

I’d sit with the men, the women and God

There by the lake of beer.

We’d be drinking good health forever

And every drop would be a prayer.

2. St. Brigid is a queer icon

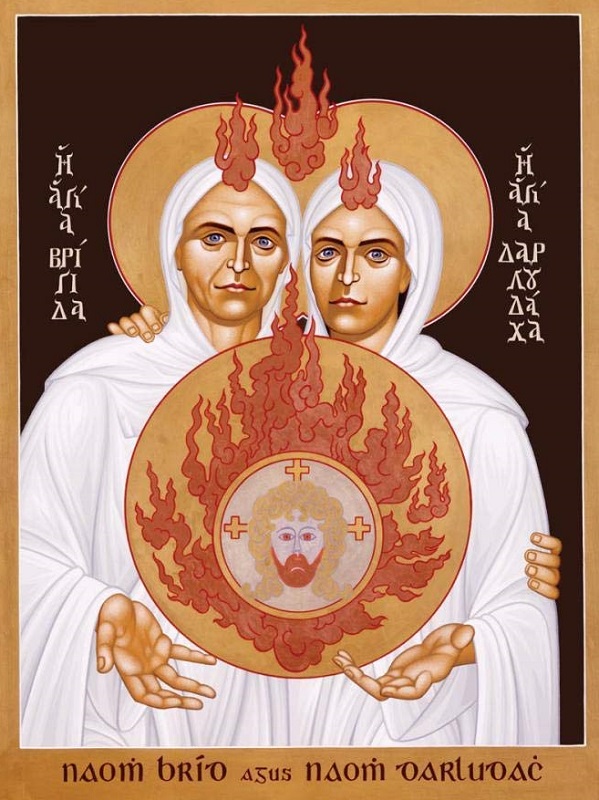

Icon by Br. Robert Lentz. You can buy his swag here.

When Brigid died, Darlughdach succeeded her as abbess at Kildare. Darlughdach is described as Brigid’s close friend, as someone who shared her bed. I have serious reservations about using modern categories to define the sexuality of people who lived before these categories were defined. But I have no problem at all exploring same-sex relationships from history that unsettle the idea that the sexual/romantic/reproductive/legal union of a cisgender woman and a cisgender man is the bedrock of human society.

I’ve known about Darlughdach for years, and I just keep getting distracted from learning more about her. I can’t tell you where to find references to her in Brigid’s hagiography or in legends of her life. I can tell you that queer theologians find meaning and affirmation in the partnership between Brigid and her successor.

3. St. Brigid was Jesus’s wetnurse, his foster mother, Mary’s midwife, or some combination of the three

Saint Bride (1913), a painting by John Duncan in which we see angels carrying Brigid of Kildare across the ocean to Bethlehem.

Saved this one for last because it is deeply nerdy and I didn’t want to scare everybody off. As you can tell, I had a career in marketing before I became a freelance witch.

There are countless stories of St. Brigid attending the birth of Jesus. As stories of religious devotion, they can be quite tender and lovely, focused as they are on the humble realities of childbirth and the role of women in ushering children into the world. But these stories are also, of course, fantastic. Someone born in Ireland in the fifth century could not have been in Bethlehem at the dawn of the common era.

Miracles are, of course, everyday events for saints—especially the early ones—but the particular nature of this miracle in interesting. In a paper I freely admit to having only skimmed at this point, Carole Cusack, a professor of Religion at the University of Sydney, notes the ways in which Brigid’s earliest biography seems to owe as much to sagas of Irish heroes and gods as it does to Christian hagiography. The relevant point here is the distortion of time, which occurs four times in the Vita Prima. Cusack compares St. Brigid to “the Dagda, who makes a year seem like a day; Nera, who ventures into a síd (fairy mound) for three days and three nights and finds on return that only a few minutes have passed; and the ultimate example of Oisin, son of Finn, who emerges from the Land of Youth to find that three hundred years have passed in the real world.”

This is all interesting to me—at least in part—because one of the difficulties of studying pre-Christian religion or religions competing with Christianity is that, often, the only sources that survive are Christian sources. There’s a sort of general assumption that monks and priests and other Christian chroniclers were inherently inimical to pagan religion but—in the case of St. Brigid, anyway—I’m no longer sure that this is true. I can almost hear medieval authors speaking in a kind of code that would have been meaningful to people who knew enough to decipher it.

Thank you for reading this far. Paid subscribers, read on to download a ritual excerpted from A Postmodern Witch’s Guide to Imbolc and get the Imbolc Tarot spread if you missed it.